People take pitch – the ability to sing in tune – really seriously. It’s made people terrified of being out of tune – and self-reported tone-deafness has never been higher. But guess what – tone-deafness is rarer than actual deafness. Pitching is far easier to learn than you think.

It’s Friday night. You’re watching the grand final of some TV Talent show. Finally – your favourite singer comes on. Dry ice coats the floor. A Roberta Flack cover starts to play.

Their lips reach the mic. And:

Oh. Oh dear. They’re…

“The performance was great, I really felt you connect with the song. But it was a little pitchy.”

“I love you. I love this. Just work a little on your pitch and come back next year.”

“Who ever told you that you could sing? The tone was all wrong, and your pitch could not have been worse!”

On TV talent shows it’s so popular that it’s become a by-word for artistic ability. It’s made people terrified of being out of tune – and self-reported tone-deafness has never been higher. But guess what – tone-deafness is rarer than actual deafness. Pitching is far easier to learn than you think.

1: Not Tone-Deaf: Sensation-Blind

There is a great misunderstanding about tuning. Most people think of pitching as a two-step system, that goes something like this:

- You hear/visualise how high the note has to be pitched.

- You sing the note.

But there is a crucial third step in between the two:

- You hear/visualise how high the note has to be pitched.

- You prepare your body to sing the note.

- You sing the note.

It is not the hearing of the note that is at fault. It is the conversion of that hearing into bodily sensation which leads to bad pitching. So you’re not hearing the note wrong – you’re feeling the note wrong. Why does this happen?

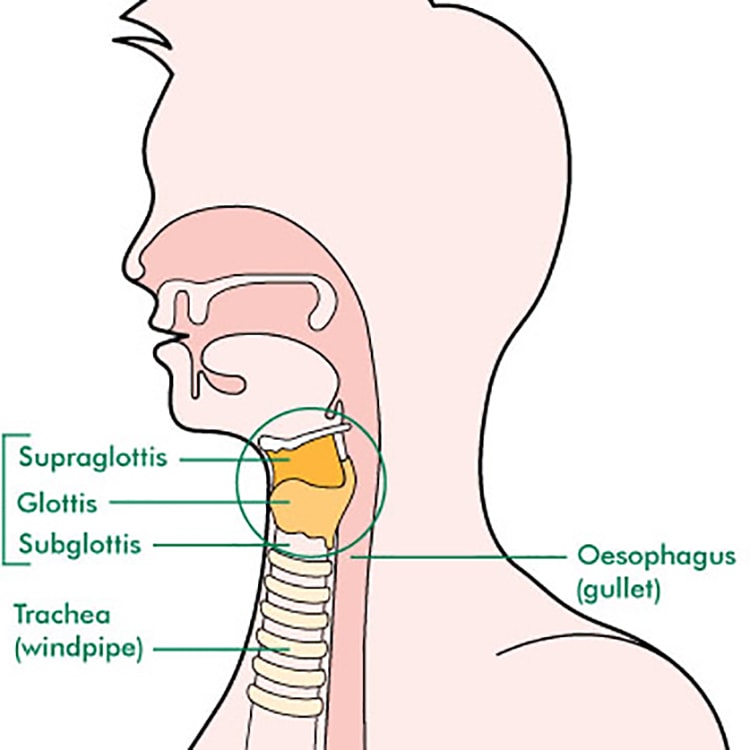

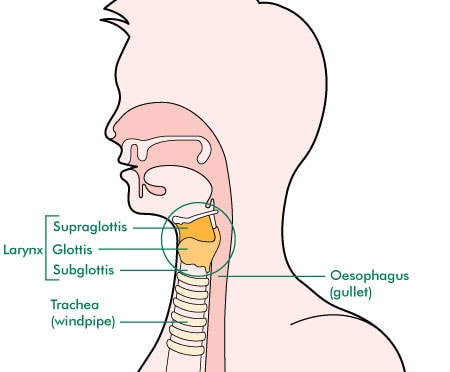

2: Larynx Position

Well, certain changes need to be made when you start singing instead of speaking. The first thing to shift should be the position of your larynx. It needs to shift a little higher than when you’re speaking, in order to match the pitch of your note with the right vocal tract length to make it resonate properly. In other words, the higher the note, the higher your larynx needs to be.

The technical reason for this is that higher pitches need a shorter overall vocal tract length in order for them to be most efficient. Think of a kazoo – short tube length, high pitched sound. And think of a didgeridoo – long tube length, low bassy sound. You can change the length of your tube by changing the position of your larynx. A low larynx position produces more of a didgeridoo sound, the higher more kazoo.

The simple fact is that when you’re aiming at the pitch, you’re most likely not moving your larynx out of its normal comfort zone, so the body then produces the note that feels most comfortable for that larynx setting – i.e. something close to your speaking voice. So you need to learn to bring the larynx higher as you sing higher. This is often very difficult for beginners to get into their bodies, so here are some triggers you can use. For all of these, place two fingers on your larynx to feel it go higher.

- Try to whistle a really high note.

- Say something in a high, children’s storyteller voice.

- Do a high, whispered ‘yay’ sound.

- Use a head voice tone, then keep the larynx there for chest voice.

- Speak in a high-pitched accent, then try this on lower pitches.

- Imagine the note feeling lighter and sweeter for the high larynx sections, then heavier for the low-larynx sections.

Try to make sure that no tension or distortion comes from raising the larynx high – it’s very easy to get the tongue tensed and get a kind of ‘kermit sound’ from the larynx being raised. If this happens, try these exercises while deliberately moving the jaw around to free the tongue.

3: Exercises

The final step of larynx movement is to get it coordinated perfectly with the pitch – moving in small motions up and down depending on where the note is going. In a stepwise motion (i.e where the notes are closer together) the larynx is easy to co-ordinate – small movements up and down the vocal tract. In this scale, I’ve put in a nasty little 5th leap at the end, which means you’ve got to bring it up and back down again swiftly at the end.

The next challenge of co-ordination is on how far to drop the larynx on the way down the scale. The larynx naturally wants to drop – gravity is pulling it down and the muscles which pull it down are very strong. So when you are trying to drop from a higher pitch to a lower pitch, the larynx will tend to overshoot and make the note go flat. This needs to be counteracted by slowing the larynx as it comes down by keeping it high. Use the scale below, and watch out for the jump at the end of each scale.

Finally, the larynx will want to drop out of position on long, held notes. Our natural speaking infections, unless we’re asking a question, tend to go down at the end of our phrases. This means that as we finish a phrase, our larynx is pre-programmed to want to drop as we sustain that final note. So – beginner singers tend to go flat on the end of long notes because their larynx wants to drop to match their speaking pattern. Keep your larynx high through to the end of these long notes.

Here at VoiceHacker, we’re all about the stuff that works. There’s a whole lot of debate about larynx position – and no doubt I’ll be getting some flak from SLS and Bel Canto teachers about advocating a high larynx. But this Vocal Hack is all about larynx mobility – getting your larynx moving away from your comfort zone and being able to co-ordinate it with the pitch. Once you can get that, you’ll never have to fear being called ‘Tone Deaf’ again.

Like VoiceHacker on Facebook and Twitter: